Ghost and The Subjective Meadow

Ghost

Three years ago my studio burned to the ground taking with it the complete archive of 30 years of my work. What survived was hundreds of porcelain shards, the remains of sculpture crushed by the collapse of the building. Also surviving were my two mules that lived in a section of the studio. They were calmly standing nearby as the building burned.

The fire came on the heels of my years-long interest in hybridity, genetics, and the manipulation of the natural world by man. I looked for what was the first man made animal hybrid and found that it was probably the mule. Mules are one of the oldest manipulations of nature by man. They are a cross between two species, the horse and the donkey. Mules have “hybrid vigor” and exhibit some of the best traits of both the horse and the donkey with some caveats. Mules are stronger, healthier, and smarter on average than an equivalent horse or donkey. Being sterile, they exist only for the labor of man. Just 100 years ago 25 million mules worked in the U.S. for farming, drayage, and battle but were quickly rendered obsolete with the mass introduction of heavy mechanical equipment. The revolution in mechanical transportation and cultivation of the land rendered mules productively and socially obsolete by the end of World War Two. By the 1960’s they all but disappeared in the U.S. Mules now epitomize the vestigial equine. Having lost their original purpose of in human economy, they are now bred primarily for appearance. Like a horse, breeders value small delicately chiseled heads and fine boned legs.

So, on a quest to find out what it would be like to be solely and personally responsible for an animal that only exists for my purposes, I set out to buy a mule. I found a yearling mule in New York State that was also the most rare example of a mule in the U.S. She is the hybrid progeny of a Poitou donkey sire and a Clydesdale draft horse mare. About 180 Poitou donkeys remain in existence, most are in France. They were developed in the middle ages and are large by donkey standards and have body hair that hangs in foot long dreadlocks. They have very large heads and heavy legs. We all have seen the Clydesdales pulling the beer wagon in the Budweiser commercials. The Clydesdale too is an endangered breed. When I bought Oopie (short for Allie Oop), she was the only Poitou/Clydesdale mule in the U.S. Now there is her half-sister. All equines are herd animals. They require a herd to be psychologically complete. Most equines will develop behavioral issues, anxieties, and health problems if they are kept isolated from other equines. I acquired another mule, Willibald, who is the result of a Percheron draft horse mated to a mammoth jack. Oopie and Willi are pretty much inseparable.

For the last seven years I have been training both these mules in the dressage riding discipline. Dressage began as the highest level of equine training for cavalry movements and maneuvers for horses in the battlefield. This is now obsolete and has transformed into sport. So we have obsolete animals trained in an obsolete military discipline.

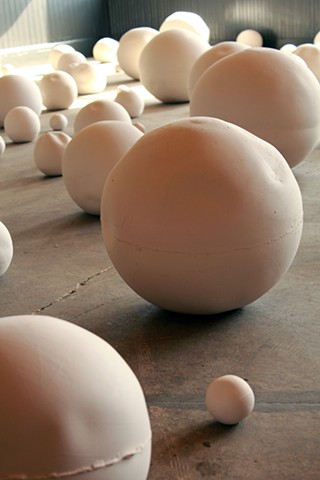

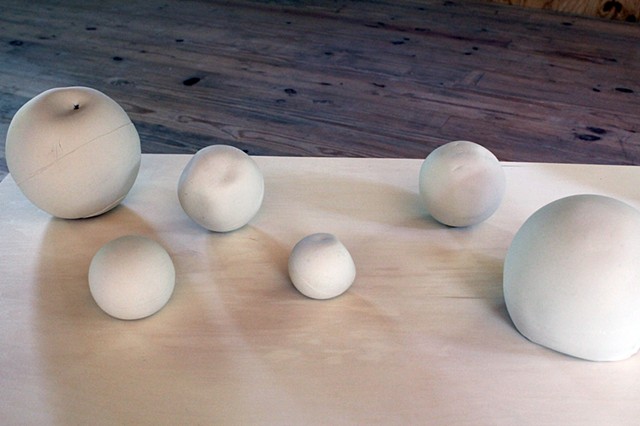

In my studio, porcelain is my material of choice. I have a new studio now that serves for the reinvention of my practice free from the crowding influence of work that no longer exists. My nearly extinct practice in porcelain is poised for a new synergy.

The teacup serves as a point of fusion, a rotational concept, for my investigation of hybridity and obsolescence. The porcelain teacup had developed for use in the various tea rituals intrinsic to elite social hierarchies. It spread from there to broader social layers. As those elitist social structures have decomposed, the social role of the tea cup has essentially disappeared from contemporary culture. The once ubiquitous industrial production of bland and banal porcelain ware continues today as a flood of plastic and disposable utilitarian ware that chokes landfills and oceans. I have chosen to use this object because it is the ceramic equivalent of the mule.

The teacup and the mule signify a sort of ghost of their own histories. In one video they perform a dressage dance interaction. The dance of the animate and the inanimate form the synergy of their obsolescence. A mule performs a piaffe (a calm, composed, elevated trot in place without forward movement) over a single unfired porcelain teacup and saucer. Eventually the cup will be trampled. The equine knows there is something underneath him. Not taught what to do with it, he tries to avoid it. Eventually the propulsion of the piaffe movement and the awkward attempts to avoid the cup causes him to lose track of where it is and he animates the inanimate at once by smashing it.

In another video a mule canters in a circle, round and round like the centrifugal movement of a potter’s wheel or a zoetrope. The mule's revolutions, pace, and direction are guided by my voice. A porcelain cup in its path may be perceived as an obstacle or a predator. To the mule, a porcelain cup has no social meaning. The mule may decide to jump over it, go around it, ignore it, or attack it.

Interspecies collaborations in art are often one-sided collaborations. The human usually uses the other without using its decision-making abilities or eliciting active, volitional contribution to the project. Desiring a more full collaborative effort, I have allowed my mules unrestricted access to my studio to investigate ceramic materials and objects. They are curious animals and want to understand objects in their environment. Actually, it is a survival skill for them. In the wild, horses evolved on the plains. When confronted with danger their best course of actions has been to run. Donkeys evolved in the mountains. For them, when danger is imminent they often will stay and fight. A mule, equal parts horse and donkey has both defenses and will make a decision to use one or the other. Curiosity in both equine species is a mechanism that enables them to understand their environment and to know what is safe and what is not.

In the performances, I will instigate the situations but the mules will decide what to do and how to finish it. Neither of us will completely understand each other’s agenda, Umwelt, or intention but we have learned to trust each other when it comes to our reactions.

As this and other collaborations between myself, the mules and teacups develop, they will inaugurate a spontaneous, intuitive, and unpredictable studio production. This synergy will be a new way for us to work to an unknown outcome. More broadly, what will remain after the collapse of all social, historical, and cultural relevance and reference to the mule, the teacup, and dressage is anyone's guess. As our societies and art have moved from these social artifacts and interactions to a more conjugated meaning of life and art prefaced in the identity of self, our historical referents may falter or persevere.